I exit the plane and walk down the stairs onto the tarmac of the Bonaire airport. Bonaire is a small island off the coast of Venezuela. The hot and humid weather is a stark difference from the rainy Pacific Northwest our group departed from earlier this morning. I turn back to make sure my newfound buds are making it down the stairs without the need of any help. We are a group of military veterans, invited to this Caribbean island to become certified open water scuba divers through "Valhalla Dive Group," a young non-profit that helps veterans overcome physical and mental injuries through scuba diving. Including myself, there are 6 vets, with varying disabilities, and I appear to be the most “able bodied.” I was invited as a last minute replacement by my buddy, Kevin. Kevin is the newly appointed student ambassador for Valhalla. I accepted the invite under the impression that I would be helping the more severely injured students, but I am quickly beginning to learn that they’ll rarely need anything from me on land, and that the amazing team of instructors have everything covered in, and under, the water. What I'm slow to realize, however, is how much help I'll end up needing on this trip.

Kevin and another student, Kieth, have diving experience, while "Chops," Aaron, Jeff, and I merely have a few hours in the pool where we've been acquainted with our gear, practiced essential skills, and gotten a feel for what it's like to breathe underwater. We will now be continuing our training in a destination that many divers only dream of.

In the airport parking lot we meet up with the other divers and instructors from the dive shop that Valhalla works with, OTR Scuba, based out of Portland, Oregon. They have a bonded group that has traveled to several destinations together, and have welcomed us with open arms and hearts. We are greeted by a man with a van, towing a small trailer for the luggage. The man has a woman and young child with him. It appears his shuttle service is a family business. The young boy, no more than 7 years old, is proud to tackle the biggest pieces of luggage, some nearly twice his size. The larger the luggage, the larger his smile. The family has dark black skin, and a quick observation shows that the island is inhabited by very dark people, and very white people. I don't point this out as prejudice, but rather as a curiosity as to the history of this island. A quick google search on Bonaire's history showed me that this Caribbean island, now a Netherland territory, has been through many changes since it was originally inhabited by Caquetio Indians thousands of years ago. If you're like me, and fascinated about how people made it to where they are today, and how places have changed along with the people that have inhabited them, you can read more about it's history on Bonaire's Wiki Page.

Once we arrive at Captain Don's Habitat, the family crew unloads our bags, again with all smiles, and as I go to tip them, I learn that Rhia, the leader of OTR scuba has already taken care of it. "She always makes sure to take care of the local help," one of her divers says. As I get to know Rhia more, I learn that she takes care of most everyone she comes across. We check into our rooms and now I'm smiling from ear to ear. Paths lined with bright colored flowers lead to a village of bungalows. Ours has a living room and kitchenette, and two bedrooms, each with two twin beds and their own bathroom. I'll be rooming with Keith, and Kevin and Chops will stay in the other room. There's a covered patio with a table that seats six or more, which will serve as a hang out spot in the mornings before we head out to breakfast and then on to diving. We share the path with small lizards, most a plain dark greenish brown, but some have bright turquoise markings that light up when the sun rays shine on their backs. Signs say: "Don't feed the iguanas" of which I only saw a few, but it didn't say anything about rolling up a tiny crumb of bread and feeding one of the smaller turquoise marked lizards by hand.

The view from breakfast is incredible, as it sits right by the water, a beautiful turquoise shoreline, reminiscent of the lizards. The bright color reaches out from the rocky shore for maybe 150 yards before it turns to a dark blue. From light to dark, represents the shallows to the deep, from 15 feet, to a drop off of around 150 feet, and from there a shelf of reef before another drop off to depths I didn't even research because it was far beyond anything we will experience.

After breakfast on day one, the first task at hands the dive briefing from one of Captain Don's dive leaders. His name is "Wilco." Wilco's skin is tanned from years of living on the island with the uniform of the day being no more than some flower patterned board shorts. He has short white hair, and a white goatee. His accent is one I hadn't heard before, and I learn that he is originally from Holland. Though I knew it the island was a Netherland territory, I am still caught off guard by these peculiar dutch accents. He told us about how the oxygen tanks work at Captain Dons, where to get the fresh ones and where to put the depleted ones. "We don't care how many you use, as long as you put them where they're supposed to go." Wilco would prove to be a hilarious guide and companion to have along for the trip. He set the tone that "This is life on the island, we don't get too upset about much. Many people dream to live a life like this, and I'm living that dream."

Captain Don's has everything you need to adventure underwater and explore the protected reef of the Bonaire coast. The rental shop has the buoyancy control devices (BCD's,) weights, and wetsuits. The oxygen tanks are stored down by the lockers near the dock, and if you don't have your own mask and fins, there is a shop right across from the rental shop to make any purchases you need. Though our costs are covered by Valhalla, I still check in on what it would take to stay here for a week of lodging and scuba diving, and it is a surprisingly affordable rate, especially since the tanks were unlimited. One of the instructors tells me this is one of his favorite parts about coming to Captain Don's, because most places charge by the bottle. That can have a big impact on a week's worth of diving at up to 4 dives per day. Mentioning Captain Don's without commenting on their staff would be an incredible injustice. From the manager, to the wait staff, to the boat captains, such as Ricardo, aka "Captain Black Sparrow," every single person made us feel like family, and by the end of the week, we all knew each other by name.

Once we have all of our gear rented, the OTR divers head out on the boat, and us from Valhalla stay on the shore to finish our training. We attach the tanks to our BCD's, check our regulators and pressure gauges, and then our instructors double check them and have us disassemble them and start again. When you're relying on this device keeping you alive underwater, it's essential that you know how to operate it properly. After a few runs of that, we gear up and head down to the end of the dock with our fins in hand. Fins are always the last thing to go on when beginning a dive, and first come off when ending. It's no fun to be a "fish out of water," and that's exactly what you are if you try to walk anywhere with your fins on. In the water the fins are essential, on land they are down right dangerous. We practice "the giant leap" off the end of the dock, which is the standard method of entry from a diving boat. Your left hand holds your hoses and gauges in place, and your right hand holds your regulator in your mouth and mask on your face. You look at the horizon and take a giant step forward and then splash into the water below.

Once I'm in the water, I'm floating because I'd already filled my BCD with air. The device has an air bladder attached to the air tank. The regulator assembly I used was called an octopus, with three air lines coming from the assembly. One is the primary breathing regulator, the second is a back up to be used if the primary malfunctions or if your diving buddy has an emergency and needs to use your air to safely make it to the surface. The third line affixes to the BCD itself and a button will open a valve and release air from the tank into the air bladders. It's standard practice to fill them with air before you get in the water, so that you float when you first get in as you wait for your diving buddy to enter. Underwater an "okay" sign with your hands is commonly used, but when you first get in the water a fist bump on the top of your dome signals to your diving buddy and boat crew that you're okay. When you're ready to descend, you either raise the valve on the bcd and press the button opposite of the fill button, or tug on a pull cord to discharge the bladders and allow the lead weights to start taking you below the surface. The slightest press of the button to add a bit more air back into the bladders will stop you from sinking, and the goal is to become "neutrally buoyant." I've heard that becoming neutrally buoyant is the closest thing to flying through the air that you can imagine. Yet, I'm having a hard time doing it. I see the instructors suspended motionless in the water, calmly surveying their new students. I'm sinking to the bottom, and then rising to the surface. I battle with this all day, annoyed and disappointed with myself that I'm struggling more than anyone else with this before realizing that it's because I'm overweighted. The weight is dropping me too fast, so I'm compensating with too much air to stop me from hitting the bottom, which shoots me back up to the top. I ditch a mere two pounds and suddenly I'm so much closer to achieving that tranquil neutrality. Still, I'm frustrated that I haven't somehow mastered this after a few hours in the water. I'm not sure who I think I am that I put such pressure on myself to learn something immediately, or at least not be the worst at it. I know, however, it's spent from a childhood of being the smallest and weakest, that I had turned around through years of hard work in the gym, leadership in the military, and camaraderie forged over years of experiences with close friends. Yet, I have since let my body go, I haven't held a serious leadership position in nearly a decade, and I live far from any of my close friends. I can't help but to feel like I'm reverting to that undersized boy who didn't really belong anywhere growing up, and is now still looking for that place, that thing, those people. As I battle through my own pity party, I look over and see Aaron. Quickly, my own problems leave my mind, and I'm awe struck at the sheer will this young man has. One of the skills that we have to learn to be certified is taking the BCD off and putting it back on underwater. This is important in case you get tangled up on something underwater. You need to know how to safely remove the device, free yourself, and then put it back on. If you're under the surface, the air bladders will be mostly empty, and the weights attached to the vest will be what keep you from floating. The neoprene from the dry suits are very buoyant, so once you take off the BCD, your body will want to shoot up to the surface. We were taught to quickly set the BCD on our knee to use it's wait to hold us at depth while we simulated freeing it from entanglements. This was not easy to do. I found myself tumbling backward and holding the BCD more on my chest one of the times. Yet, when I look over at Aaron, he is doing this with only one arm and one leg. Aaron stepped on a claymore mine in Afghanistan, losing his right arm and leg. Yet, here he is, breathing underwater and passing the tests necessary to become a certified open water diver. How little I really have to complain about. From then on, I was just happy to be in the water, and happy to be there with such amazing people.

My next obstacle, funny enough, would actually be with being too excited. Once we finish the days repetition of skills such as BCD removal, shared breathing, mask clearing, we finally get the chance to swim past the shallow water and toward the reef. Though the shallows had a decent amount of beauty, it was nothing like what presented itself to us in the deeper waters. Swimming toward 30ft opened up an entirely new world, and my heart races as my mind processes the millions of new bits of data. The bright coral, the schools of colorful fish, the spotted eels swimming through the sand of the white ocean floor. These are all things I've only seen on the Discovery Channel, yet...here I am. I am BREATHING UNDERWATER!! Most everyone has split fins that are very flexible, good for slowly moving through the water at a leisurely pace. My fins are solid and rigid, and my stocky legs can use them to propel me through the water in a way that made me feel like I was truly flying. I keep my legs together and kick as if my feet are a dolphin tale. I swim sideways in a big circle to survey my team members. I do barrel rolls. The many dreams that I'd woken up from disappointed when I learned I couldn't fly have finally come true. I am flying...under the water. However, this comes at a cost. Your time underwater is directly related to your air use, and the physical output to swim like a dolphin greatly increases oxygen use, and decreases the time underwater. The last thing you want to be is the person who runs out of air first and causes your team to have to return with air still in their tanks, and time they could still be exploring the ocean they traveled to see. "We need to get you to settle down underwater." was the first comment I received from Marissa, the founder of Valhalla Dive Group. Damn it. I'd like to eventually be able to come back and help vets like Aaron and Jeff, who need extremely focused dive buddies to ensure they stay safe underwater. "I need to get some more of this excitement burned off under there, I just can't help how amazing it feels to fly for the first time. But I'll settle down. I can focus when it matters." I sensed my reply was received with a bit of skepticism, understandably so. I've had so many changes in recent years that my ADD has been going nearly unchecked and my mind will rattle off in a thousand different directions with millions of thoughts invading throughout the day. It's something that I am very self conscious of, and only a few things really help me with it. Photography, writing, general labor, and cycling are the things that pop to mind first and foremost. Meditation, however, had helped immensely for a while, likely more than anything I've experienced. Yet, about a year into the practice I suddenly had an extremely hard time doing it. I've tried to get back into it, but every time I sit down to do it, my mind turns up the volume on those thoughts rather than identifying the thoughts, sensations, emotions, and letting them go. This is where scuba comes back full circle.

Meditation is all about breath. Deep breaths, deeper than you ever knew you could breathe in, and pushing that breath out until there's nothing more to push out. All the while, working to clear your mind of thoughts, keeping focused on that breath. When thoughts arise, you let them go. A meditation group leader once told me to imagine a pond in the middle of the forest, and when the thoughts or sensations arose at the surface, you learn to identify them for what they are, and let them go. When you ask someone what the essentials to survival are, they often say "food, water, and shelter." So many forget air, and when you remind them, they'll usually respond something along the lines that "Well that's a given." What that tells us, is that air, and our breath along with it, is taken for granted. We will die much faster, nearly immediately, without air, while we can last for days on end without the other essentials. In the moment, air is all you need to survive. During meditation, you are giving your body what it needs the most, and reminding it that it has plenty of it. If you have an abundance of what you need most, then everything else should be okay. Every other problem should be able to have some sort of resolution, because you have your breath, and in this moment, that's all you need.

Scuba diving is mediation. Of all the factors to pay attention to under the water, buoyancy control, your gear, your location, marine life, physical hazards, your breath is the most important. The first instinct during distress is to jet up toward the surface, spit out your regulator, rip off your mask, and take in a giant breath of air. Yet, as long as you have air in your tank, there is no need to panic. Even if you don't have air in your tank, your diving buddy should be with you and the two of you should be able to safely surface together using the skills that are taught in the basic certification classes. This is why we practice "losing" our regulators and staying calm underwater as we reach back and put them back in our mouth. This is why we practice sharing air with each other. This is why we practice taking off our BCD as if it were caught on something. This is why we fill our masks with water and practice clearing them. Because, as long as we have our air, we can breathe. As long as we can breathe, we can take the time to think clearly to resolve any situation that we may have gotten ourselves into. Taking this information back to life on the surface is the real lesson here, and that's one of the most alluring things about scuba diving to me. That the lessons learned under the water will translate in ways above the water that can truly be life changing. When I encounter a problem my mind often races and fills with anxiety or anger, inflating the problem to something much larger than it is, perhaps with enough practice of staying calm underwater...I can remember that my breath is all that I need.

All of this being said, though having air under the water may be all that you need to survive in the moment, there several other factors that require focus to ensure that the dive goes safely. I already mentioned an understanding of your gear, such as buoyancy control and proper weighting, but it's equally if not more important to understand how to manage your air, how deep you can go on the air that you have, what breathing the air at those levels does to your body, and how to come back to the surface safely. This doesn't include awareness of the environment nor an understanding of the forces of the water you're diving in. Learning and understanding all of these things are important to ensure you and everyone with you is safe under water, and they are also just that much more to be focused on underwater, which leaves no time for invading thoughts. Recognizing this, makes me want to get back under the water any chance that I get.

Now that I've gotten all that generic blubbering out of the way, I'll get back to our actual trip. I told you about Aaron, working with missing two limbs, but I haven't yet mentioned Jeff. Jeff is paralyzed from T-5 down from a vehicular accident while he was in the Navy. Experiencing Jeff's attitude in the airport quickly showed me that he was not a person to let his disabilities define him. Jeff rolled toward the escalator and an airport staff member said: "Sir, you can't go down there!" Jeff turned his chair around, backed it up to the moving stairs, and said "You gonna stop me?" Jeff grabbed onto the rubber black railings and held on, riding down the escalator backward as the staff member stared in awe. He didn't let this stop him from diving under the water with an air tank strapped to his back, either. Rather than getting help carried down the stairs into the water, Jeff tosses his gear into the water, rolls his chair to the end of the dock, and flings himself into the water. The instructors and helpers help him put on his gear, and have learned that strapping his legs behind him help out with his buoyancy control as well as keeping his legs from spasming. He swam upright, like a big ol seahorse, and it was absolutely amazing to see him underwater, propelling himself forward with his arms. By the end of the day, an underwater photo of him became his profile picture on facebook, and reading the comments put a big old warm and fuzzy in my heart. That's what this is all about. I have so much learning of my own to do, but if I can get enough experience under my belt, and enough excitement of exploring the new world burned off, I'd Love to be back in the water someday, helping someone else like Jeff or Aaron get the opportunity to experience this magical feeling.

By day three, all of us were officially open water certified. Jeff and Aaron stayed back on the shore dives, and Chops, Jeff, Keith and I went out on the boat. On our very first official dive as open water divers, we were able to do a shipwreck dive, reaching depths of nearly 95 feet. We didn't push our luck and go through the ship, as not all the instructors were keen on us doing this for our first dive. I'll admit, the night before I was heeding their concerns and didn't want to make them uncomfortable, when Chops pulled me aside and set me straight. "Dude...we may never get the chance to something like this again. You think you can do this?" "Definitely, man." I replied. "Well, then do it. Stop living for everyone else and live for yourself." Like I said, it was me that ended up needing the help on this trip. After our first two days on the shore dives, diving as far as 60ft, and gaining confidence in our gear and our abilities, I knew I could go further. Yet, I noticed one of the instructors felt uncomfortable with us going, so rather than speaking with confidence that I could make it safely, I said I would skip it. Yet, Chops was right. When would the next chance be? Whenever I think of things in this perspective, I think back to my brother and sister's deaths. When was their next chance to do anything? They didn't have another one, and I may not either. "Let's do it."

The dive went flawlessly, we stayed within our limits and kept to the outside of the ship. Merely seeing a ship that had been sunk after being abandoned with copious amounts of cocaine on it decades ago was still an incredible experience. We also got to see our first Tarpon! Tarpon are anywhere from 4-8ft long, and though they eat smaller fish, they are harmless to humans. The additional atmospheric pressure at 90+ feet was still barely noticeable, but I did feel as if I may have had a bit more resistance as I filled my lungs, and a bit of help pushing the air back out of them. What was really noticeable was how much more quickly we depleted our air. It was our first real lesson in how going deeper isn't always better, because it's a trade off for time under water.

Our next dive was a night dive and that brought forth an entire new level of meditation. I have a beard, and would use a special wax on my mustache to help the mask seal. I forgot to apply it on this particular dive and my mask kept filling with water. Being in nearly pitch black water at 40ft deep, with only a handheld flashlight to light your way is one thing, but then when your mask keeps filling up and you're blind to boot...it takes a whole lot of woo-sah action to remain calm and enjoy the experience. No matter how friendly I just said the Tarpon were on the wreck dive, it doesn't change the pucker factor when you're looking out of one eye in the dark and suddenly a fish that's as big as you swims into the beam of your light trying to hunt fish in it!! Wilco was leading this dive, and was able to show us a pair of seahorses, one red and one yellow. Their tails were wrapped around a piece of coral or some type of underwater vegetation, and they swayed back and forth as a group of bubble making onlookers with flashlights came to observe them. We saw a giant spiny lobster hanging out in a small cave, and some members of the group got to see a pretty good sized moray eel.

The next day we were able to help spot lionfish for those that were hunting them. Though the reef is protected, hunting lionfish is actually encouraged because they are an invasive species, brought by humans, and are devouring the native fish of the reef. On these dives, Chops and I were able to reach our goal of over 100ft deep. We had come so close on the ship dive, that we just had to make sure that we broke that barrier before we left. It's a military thing. Speaking of which, the instructor that wasn't excited about us going on the shipwreck dive later told us: "You know, I think I've been treating you guys like civilians, and it's hard to realize that you guys aren't average people." That made me smile a bit, and I responded that this very attitude can get us in trouble, but yeah, these aren't average people you're working with here.

Amongst my favorite things to see underwater would be puffer fish, a moray eel, the spotted eels, the seahorses, a 4ft+ barracuda, countless variations of trumpet fish, schools of dark blue fish and silver/yellow fish that I would swim through, flying fish sailing about a foot above the water for nearly thirty yards, and my heart almost left my body when we alerted of a sea turtle. He wasn't very big, a hawksbill I was told, but to float above him and watch as he carried on his turtle day of foraging in the reef for little bits to munch on was a true dream come true. By then I had really gotten a better understanding of the utilization of my lungs underwater as my own buoyancy control device, breathe in and you'll rise, breathe out and you'll sink. I hovered around the little guy and took as many mental pictures as possible. Cheech, one of the instructors with us, had his underwater camera and captured a few of the both of us. I'll make sure to share those whenever he gets them to me. I believe he has a website, and I'll share a link so that you can see all of the amazing creatures and divers that he was able to capture on our trip. Speaking of divers, I have to include them in my favorite sightings. The excitement on Chops' face after every new fish he spotted. Aaron making the shark signal on his head and pointing to the nub that was once his right arm. Keith swimming to the surface with a hefty lionfish on the end of his spear, Kevin floating in perfect neutral buoyancy as his two prosthetic legs shine bright below the surface. The ocean obviously has such a wide variety of marine life, but I'm not sure if it's had such a wide variety of human life as this bunch.

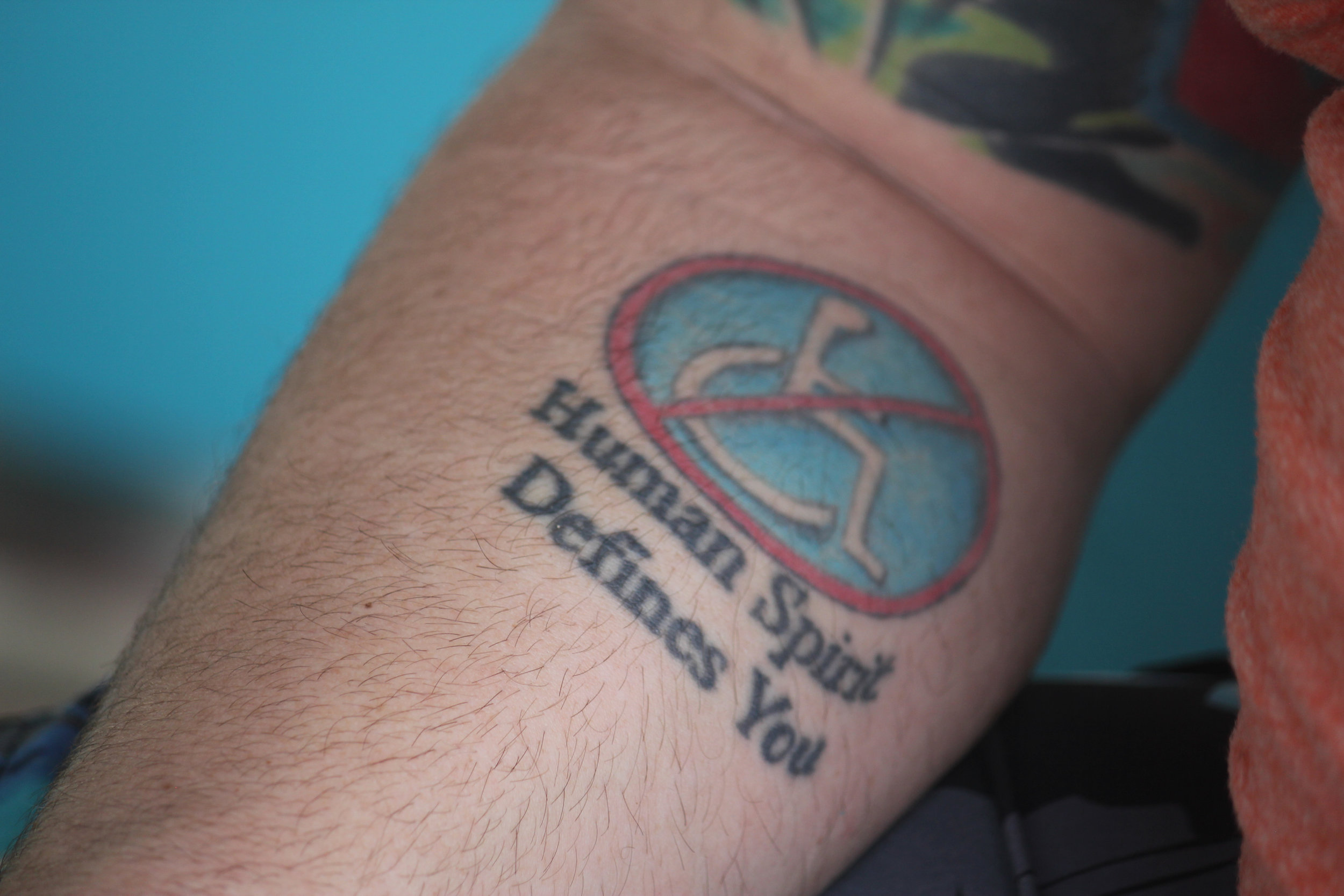

Below, I've included some of my favorite above water photos of the Valhalla Crew. You'll see the Vets; Kevin, Chops, Keith, Jeff, and Aaron. Next are the staff, Cheech, Karen, Nic, Rory, Jasmine, Rory again because that photo is too cool. Then Marissa, the founder of Valhalla, and finally Rhia, the OTR Guru. Oh, wait...there's Wilco and Ricardo as well! Haha. I could say so much more about each one of these amazing people that I befriended on the trip, but I'm going to let the photos do most of the talking here. Below these photos are a few shots of the tattoos that tell stories of their own.

When I bring my camera along, I always hope to be able to give those with me a bit of a gift. It's like my mom and her crocheting, every where we go she has to give somebody something. For me, it's a photo that I hope they'll cherish, or at least appreciate. Sometimes it's the words along with the photos that they appreciate more. I'm still finding my own path along this crazy thing called life, but taking my camera with me to capture a story and sharing it with anyone who may be inspired by reading it, seems to be where my path keeps leading me. With each new place I see, and new relationship I form, I feel that I'm doing what I'm meant to do. Explore. Learn. Grow. Share. I feel fortunate for having so many wonderful people in my life who make these things possible. I truly have lived a life I could never have dreamed of. For that, I am very grateful.

With that being said, make sure to visit www.valhalladivegroup.org and share this link with any ENABLED veteran who may be interested in such a life changing experience.

Thank you again to Marissa, Rhia, Karen, Cheech, Nic, Jasmine, and Rory for giving us an experience to remember for a lifetime. I can't wait to get back out and under the surface with any and or all of you!! Same goes to all the friends I made through Valhalla, and the staff at Captain Don's. Spending a week together and having an experience like this makes friends for life, in my book.

Much Love,

-Rob K.